Artificial Intelligence, Illustrators and Copyright

The use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools in the creation of all kinds of artwork – visual, textual, musical – has accelerated over the past year or so. The rise in AI-generated visual artworks has been fuelled by the development of new text-to-image tools, such as DALL-E, Stable Diffusion and Midjourney.

The use of AI in the production of artwork is now an area of intense debate and is central to a number of legal cases, but for various different reasons – we’ll look at some of the issues here.

How Do AI Image Generators Work?

To understand the issues, it is important to grasp how AI image-generating tools work. Stable Diffusion, for example, is image-generating software that is “trained” on vast databases of existing images and their associated text descriptions, such as the Laion-5B image dataset, which consists of 5.85 billion tagged images.

The Stable Diffusion software analyses these datasets and, by connecting the descriptive text with the images, progressively learns not only what each of the pictorial elements represents, but also what expressive visual techniques have been used to produce the images – even, for example, the names of artists and their signature styles.

When users provide a text prompt input for the AI tool, it creatively generates a series of new images informed by the database that it has analysed. Users can then select one of the resulting images and refine their text prompt to iterate the process until the AI tool delivers an image that the user is happy with.

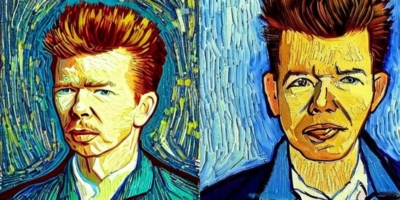

Instructing the Stable Diffusion Playground web tool to create “a portrait of Rick Astley in the style of Vincent Van Gogh”, for example, resulted in the images below – though each run will produce a different set of images, even with the same text prompt.

AI images generated with the text prompt: “a portrait of Rick Astley in the style of Van Gogh”

Whose Images Train AI Models?

Using existing images that have been captured in large datasets to train AI models is a contentious issue, however. This is particularly the case when some datasets have been produced simply by crawling the internet to copy images, without first requesting explicit permission that the images be used for AI training.

Copyright laws vary from country to country, but in general existing copyright laws place restrictions on the use of copyrighted imagery while permitting some form of “fair use”, notably for non-commercial research purposes. Often, image-text datasets produced by academic researchers for the development of machine learning tools would fall into the non-commercial category, but many of the resulting AI tools that have been trained on those datasets, such as Stable Diffusion, are commercial products. Because the use of the images has become commercialised, this has enabled copyright holders to file lawsuits.

One of the first legal cases regarding AI image creation came about when a number of artists launched a group class-action lawsuit in the US Federal Court in January 2023 in response to their artworks being used to train AI models. The three defendants were Stability AI, which makes Stable Diffusion, as well as two companies that provide text-to-image creation tools powered by Stable Diffusion technologies: Midjourney and DeviantArt.

A further lawsuit was filed against Stability AI in the UK a week later by stock image giant Getty Images, which sought to prove that Stability AI had “unlawfully copied and processed” Getty’s images and the associated metadata in order to train its AI model. The claimant presented images generated by Stable Diffusion that included the Getty Images logo, which strongly suggested that the AI model had been fed imagery scraped from the Getty Images website.

Instructing the Stable Diffusion Playground web tool to create “Getty Images crowd scene”, for example, resulted in the image below – clearly the training dataset includes rights-restricted images.

Although US and UK law both allow for the “fair use” of copyrighted artwork, they enact this in different ways. The two different legal jurisdictions overseeing the lawsuits will have an effect on how the two court cases play out.

These pressing concerns around the use of copyrighted images for training AI models are now being discussed by lawmakers around the world. The rulings of judges and the introduction of new laws will no doubt clarify some of these issues in the coming months and years, but artists, researchers and corporations are fighting to defend their respective rights now.

AI image generated with the text prompt: “Getty Images crowd scene”

Artists’ Rights: Do Not Train

Organisations such as the Association of Illustrators recommend including explicit instructions forbidding the use of artworks for the training of AI models. For example, the AOI’s website Terms & Conditions now include the following clause: “Other than strictly as permitted by law you must not carry out on our website or its content any automated data mining, web scraping or other processes for extracting data or images.”

Adobe is also proposing that digital images contain explicit “do not train” tags, but artist-rights campaigners claim that existing copyright law means that artists should not have to explicitly opt-out of their work being used to train AI. Instead, they argue that AI tool creators must instead seek explicit prior approval for copyrighted work to be included in training databases.

The Have I Been Trained website enables artists to check whether their images are included in the Laion-5B dataset and allows users to opt out of training, which some dataset producers will honour. A quick search for “stock photos” clearly shows that the major stock photography websites, such as Alamy, Getty Images, iStock and Shutterstock, have all been scraped for content.

Who is the Artist-Author of an AI Artwork?

Copyright, in most countries, including the US and the UK, is automatically assigned to the artist-author of the work. (Unless the artist is working as an employee of a company, in which case the company retains copyright of the artwork.)

Yet the question of the ownership of AI-generated artworks – ie who holds the copyright – has been the subject of much debate. In March, however, the US Copyright Office issued a helpful policy statement that clarified its position on copyright regarding material generated by AI.

In short, the guidance confirms that, in the US at least (though other countries may well reach similar conclusions), only human-produced material can receive copyright protection. For example:

- Any artwork generated solely by text prompts is not copyrightable.

- When AI imagery is combined with “human-authored” imagery, the elements that were generated by AI will be excluded from copyright protection.

- Artwork produced using AI-generated imagery as a starting point, which is then reworked by a human author, will receive copyright protection, but only if the AI imagery has been modified in a sufficiently creative way to constitute an original work.

The US Copyright Office’s argument relies on two points:

- Giving text prompts to an AI tool is the equivalent of issuing a brief to an artist, with the original artwork then being authored by the AI tool, just as an artist would be considered the author of a briefed artwork no matter who briefed them.

- In US law, copyright can only be assigned to humans, so even though the AI tool is considered to be the author of the original artwork (not the human feeding it text prompts as a “brief”), the software cannot be granted copyright, therefore the resulting artwork will receive no copyright protection.

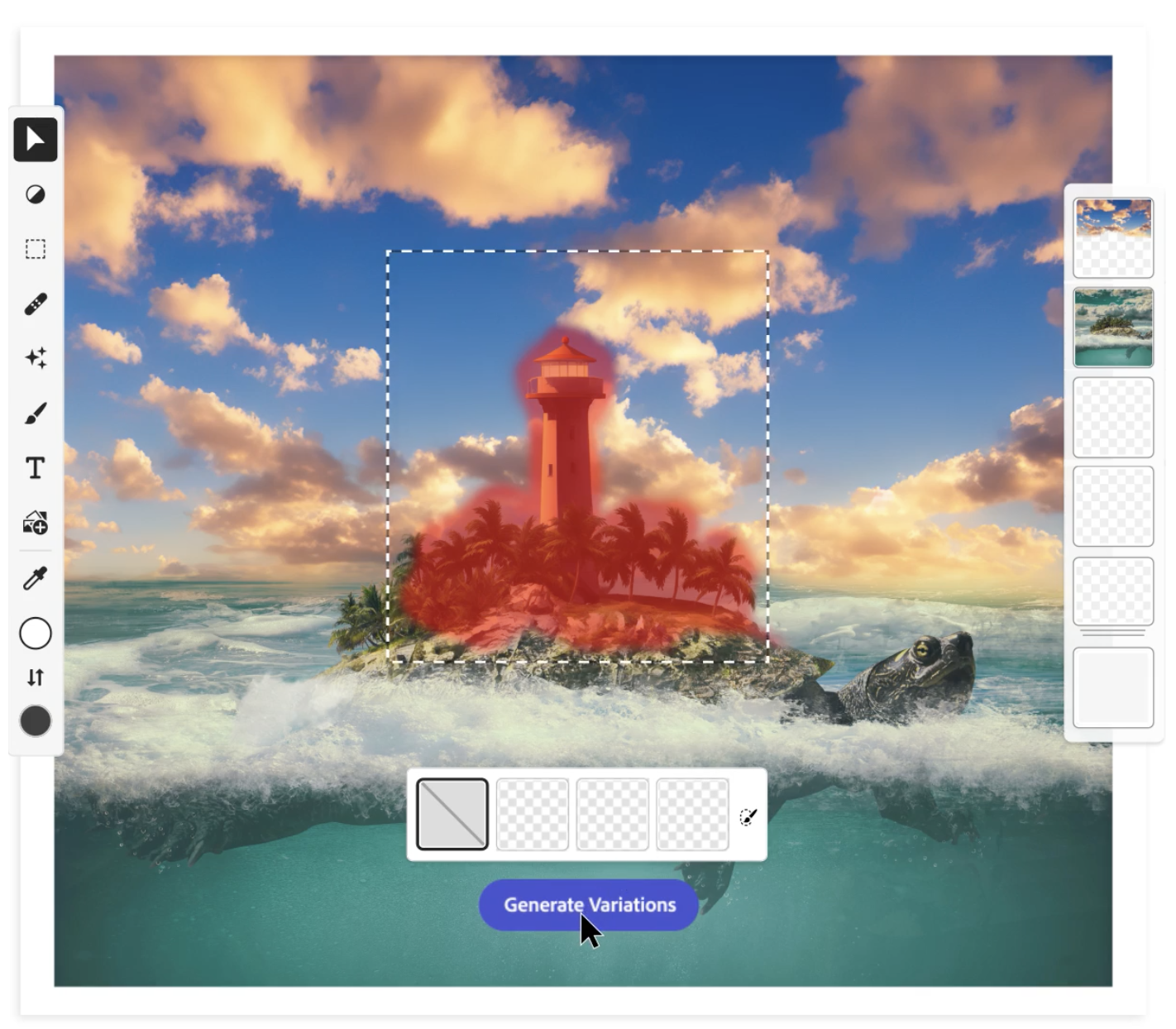

Incorporating AI into Production Workflow

There are very many generative AI tools available, but perhaps most pertinent to professional artists is Adobe’s recent announcement of Firefly, “a family of creative generative AI models coming to Adobe products”, which will allow artists to “use everyday language to generate extraordinary new content”. The Firefly AI model has reportedly been trained on Adobe Stock images and public domain content, so Adobe claims that it does not infringe existing copyright laws.

Adobe Firefly promotional images

One issue with Firefly, however, is the US Copyright Office’s application of copyright law: if the artist relies on simply providing text prompts that Firefly then uses to generate images, the resulting artwork will not be considered the work of the artist (or Adobe) and therefore will have no copyright protection.

Any artist making use of tools such as Firefly should bear in mind the US Copyright Office guidance. Artists should therefore ensure that any artwork they produce with such generative AI programs is sufficiently “human-authored” – reworked by the artist to such an extent that it is considered an original artwork – if the artist wishes to receive copyright protection for that artwork.

The implications for commercial illustrators are significant; if an artwork is not eligible for copyright protection, the artist is not able to offer clients an exclusive licence for the use of that artwork.

Furthermore, here at Folio we are starting to see an increasing number of clients include clauses in their contracts that expressly forbid the use of AI-generated imagery in commissioned artworks. Here are just a couple of examples of the kind of wording we are now encountering in contracts:

- “The Artist agrees not to use AI-generated images, artwork, design, or other visual elements for the Commissioned Works without the Client’s prior express approval.”

- “The Artist warrants that the Commissioned Works are and will be the Artist’s own original work and not […] generated solely or in part by use of artificial intelligence technologies.”

Again, the implications for commercial illustrators are significant; artists must bear these legal restrictions in mind when creating commissioned work, and even consider potential contractual issues when they choose which digital applications to use if some software packages automatically include AI-generated tools.

If artists do use AI-generated imagery when creating artworks, it is imperative that they keep track of this usage so that clients – either current or future – can be informed should they wish to licence the artwork.

Content Credentials

To clarify the status of digital images, a consortium of major media and creative technology companies is backing the Content Authenticity Initiative. This initiative, and the resulting Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA), aims to create digital “content credentials” tools that will allow authors to tag digital images with metadata information that explicitly states both attribution and provenance details: for example, who the author is and whether any elements were produced using AI.

This initiative was set up as an attempt to provide verifiable information regarding the veracity of digital images, such as whether a documentary photograph is effectively untouched from the moment of capture or whether it has been manipulated in post-production using AI tools or “deep fake” software. The initiative could also help visual artists specify whether any compositional elements in an artwork were generated entirely by AI, thus clarifying the copyright status of the artwork.

Such information will be vital in the future because, without copyright protection, which human-authored work automatically receives, there is no legal way to prevent unauthorised use of artworks. Artists should be mindful of this if they wish to protect their rights when utilising this new breed of AI image-generation tools.

Updated February 2024 to include examples of wording from client contracts that exclude the use of AI-generated imagery.

This article is for information only, and not for the purpose of providing legal advice. Always consult a solicitor if you require legal advice on a specific matter.